Lesson 1) Disney’s Influence: “Founding” Fairy Tales

Before I say anything else, I would like to thank a number of people for helping me put this wonderful activity together.

A HUGE thank you to Professor Batyaeva, Professor Cattercorn, Professor Morgan, Professor Honeysett, and Professor Jericho Penrose (our new hire!) who wrote two lessons each. You all went above and beyond the call of duty and I can't thank you all enough. Many of these lovely professors came in at the eleventh hour to save my behind!

A HUGE thank you to Professor Hackett, Professor Maddox, Professor Proctor (our new hire!), Professor Turing, and Professor Polgara. Many of you were also pulled in at the eleventh hour and I also can't thank you enough for helping me make this happen.

I would also like to thank all the professors who contributed to these lessons in the form of "guest" appearances. Your insights on the material provided an additional layer of analytical richness and for that I am extremely grateful.

Finally, thank you to Karelin Elladora Prewett who graciously agreed to host the Disney Lit Week screenings for us. They were a huge success!

Moreover, at the end of every lesson, you will be provided with a link to a Google Doc where you'll be able to discuss the lesson with your fellow peers and HiH staff and professors. This is entirely for your own amusement and is not mandatory whatsoever. Every day I will post the links to the screenings and the discussion page so that people are kept informed.

Please read the Course Description for Disney Lit Weeks as it contains important information about how the next two weeks are going to work! Moreover, be sure to read all content within each lesson, as you never know what you might be tested on. For example, each lesson contains visits (in the form of speech bubbles) from other professors who briefly discuss their own HiH class in relation to the Disney material. Not only will be this be helpful for you to review, but also beneficial for your future studies here at HiH! This lesson contains visits from multiple professors including: Professor Lucrezia Mikhailovna Batyaeva (Potions), Co-Professor Balfour Levintree (Charms), Professor Rose Honeysett (Magical Art), and Co-Professor Jericho Penrose (DADA).

Your (long-awaited) syllabus for this week:

Week 1: Fairy Tales

Lesson 1 (May 8) – Disney’s Influence: “Founding” Fairy Tales (Snow White, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty)

Lesson 2 (May 9) – Under the Sea (Little Mermaid)

Lesson 3 (May 10) – Tale as Old as Time (Beauty and the Beast)

Lesson 4 (May 11) – A Whole New World (Aladdin)

Lesson 5 (May 12) – Honour to Us All (Mulan)

Lesson 6 (May 13) – Almost There (The Princess and the Frog)

Lesson 7 (May 14) – At Last I See the Light (Tangled)

Lesson 8 (May 15) – Let it Go! (Frozen)

Week 2's syllabus will be released on May 16, when Disney Lit Weeks 2 goes live!

Note: There are a few footnotes in the section on Snow White (the blue numbers) and the actual notes can be found at the end of the lesson.

Finally, because the first lesson is on three Disney movies, it will be *considerably* longer than most of the

other lessons. So do sit back, play some Disney music to set the mood, and enjoy the ride.

EH

http://www.hogwartsishere.com/emmahart/

https://www.facebook.com/emmaharthih

https://www.facebook.com/HiHMagicalLiterature

Disney’s Influence: “Founding” Fairy Tales (Snow White, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty)

Walt Disney: The Man, the Legend

While there are countless themes within all of Disney’s movies, there appear to be two that unite them all—the motif of the orphan (the loss of either both parents or one) and the trope of magic (both light and dark). Throughout the next two weeks, you will no doubt pick up on these recurring themes, but I wanted to make a few points about them here.

The Orphan Motif

As someone who suffered a harsh and lonely childhood, often subject to the whims of a tyrannical parent, Walt Disney’s choice in introducing many of his main characters without parents—or showing us the loss of one at some point in the story—should come as no surprise. At the age of nine, Disney was forced to deliver newspapers in the bitter cold for his father’s paper route in Kansas City—an experience that continued to plague him with nightmares for the rest of his life (Schickel 55). Although Disney’s father was clearly not cut out for parenting, Disney’s mother, on the other hand, provided little rays of sunshine as often as she could.

However, Disney would face yet another trauma involving a parent, though this time as an adult. Sadly, Disney’s mother’s life ended at the age of 70 (less than a year after Snow White was released in theatres). Situating his parents in a lovely home on studio property, Disney gave his mother everything she could ever want. However, in her letters to her daughter, Disney’s mother repeatedly remarked on the smell of smoke coming from inside the house. Although multiple repairmen attempted to fix the situation, Disney’s mother eventually died of asphyxiation. Traumatized by his mother’s death for the rest of his life, Disney would then channel his loss into multiple films, films that often focused on the premature death of the protagonist’s mother; for example, Bambi, which depicts (off camera) Bambi’s mother being shot by a hunter—a cinematic moment that certainly haunts me, and perhaps many of you, until this day. Given Disney’s difficult childhood, and the unfortunate loss of his mother, it is no wonder that Disney drew on the trope of magic, both light and dark, in order to paint a beautiful story.

The Trope of Magic

When interviewed about his films, Disney remarked that he

“believed fantastic things must be based on the real—that it is first necessary

to know the real” (Wright 102). Disney was certainly a man who faced a harsh

reality growing up. Once described as a “tall, sombre man who appeared to be under the lash of some private demon,”

Disney was born into poverty, both emotional and financial. Finding solace in

his artistic talent, Disney took art classes before he left home at 16 to join

the Red Cross Ambulance Corps during World War I. Setting up shop in Kansas

City (living in the studio, eating beans out of a can), Disney explored his love

of animation. Finding it difficult to break into the industry, he then moved to

Los Angeles and partnered with his older brother. After his cartoon “Oswald the

Rabbit” was stolen from him, Disney

eventually ‘gave birth’ to that loveable figure known throughout the world as

Mickey Mouse.

In his earliest conception, Mickey was everything Disney

imagined (and needed) him to be: confident, chipper, and cruelly mischievous if

the occasion called for it (which it so often did). But above everything, Mickey,

for Walt, represented a shining beacon of hope for the American Dream in the

face of the extremely bleak Great Depression (1929-1941). Given the harsh

reality of Disney’s childhood, and the world in which he grew up, it is no

wonder that Disney’s films used magic to offer audiences not merely an escape

from the world, but a way of seeing the

world anew.

In his earliest conception, Mickey was everything Disney

imagined (and needed) him to be: confident, chipper, and cruelly mischievous if

the occasion called for it (which it so often did). But above everything, Mickey,

for Walt, represented a shining beacon of hope for the American Dream in the

face of the extremely bleak Great Depression (1929-1941). Given the harsh

reality of Disney’s childhood, and the world in which he grew up, it is no

wonder that Disney’s films used magic to offer audiences not merely an escape

from the world, but a way of seeing the

world anew.

In classic fairy-tale traditions, “magic intervenes on behalf of an oppressed person to ameliorate a dreary experience” (Wright 103)—something that we will be discuss further in Magical Literature come Year 4. While some film critics declare that Disney removed the powerful fantasy of the märchen[1] and replaced it with “false magic” (Stone 16), our childhood conception and understanding of magic no doubt formed through watching Disney’s films (Harry Potter notwithstanding).

In Disney’s films, magic serves both a didactic (instructional) and entertainment function. Magic can also be used for evil. In Disney’s Sleeping Beauty, it is Maleficent’s evil curse that places Aurora in an eternal rest (a similar effect that the Draught of Living Death might induce), but it is Merryweather’s redemptive magic that provides the “loophole” for Aurora’s potential awakening. An awakening, as we all know, that can only come about through “true love’s kiss”—which is not only Princess Aurora’s saving grace, but also Snow White’s.

Disney’s Muse: Snow White, “The Fairest of Them All”

In 1937, Disney released Snow

White and the Seven Dwarfs, adapted from a traditional märchen to produce the first full-length animated feature.

Although generally adhering to the Brothers Grimm version, Disney drew on

popular American culture to supplement the story.

By 1934, Disney had already won four Academy Awards and employed more than 100 people; however, he knew that the only thing that would generate a large income was a full-length feature. Out of all stories to choose from, why would Disney bank his entire future (including his personal savings) on the 1812 Brothers Grimm fairy-tale Snow White (Schneewittchen)?

Following a special dinner with his colleagues, Disney met with his chief animators on the sound stage of the studio and acted out (his version) of the entire plot of Snow White—every character, and even every song, was already composed in Disney’s mind. His rendition of Snow White “brought tears to the eyes of his staff” and it was at this time that he announced that Snow White would be the studio’s first feature film (Thomas 65).

Initially, the world thought choosing Snow White was silly: many newspapers famously dubbing the idea as “Disney’s Folly”; no one thought that people would willingly choose to sit still through an hour and a half cartoon. But Disney felt he had the “perfect story”—the romance, the pathos[2], the action, and the comedy.

As a young boy, Disney had first seen the story Snow White in 1916, in the silent film starring Marguerite Clark (Thomas 65). Disney enjoyed it so much that he had wanted to see it again and again (Bauer 18). Disney assumed that Snow White’s story was one that was known and loved all over the world and he wanted to capitalize on a “recognizable” story—a plot that was not “too fantastic”, involving a realist setting with a dash of magic. Moreover, Disney thought that Snow White perfectly reflected and embodied everything coming out of Hollywood in the 1930s: romance between an attractive hero/heroine, an evil villain, comedy, and—of course—a happy ending (Quirk 65).

"Classic Disney" (Disney Formalism)

(This section is extremely important, especially in relation to The Princess and the Frog lesson later this week, so please pay extra careful attention!)

Snow White ultimately gave birth to what became known as "Classic Disney", or as later film scholars asserted, "Disney Formalism". This term referred to the formation and continuation of a specific aesthetic style. It began with Snow White and carried forward with Pinocchio (1940), Dumbo (1941), and reach its peak with Bambi (1942). These films, according to Watts, "established the creative high-watermark of the early Disney Studio" (1997: 83). Although we might often think audiences termed the phrase "Classic Disney", the phrase was first used with the emergence of the home video market. You know how Disney continually releases its "Classics" under Platinum and Diamond editions? This marketing strategy all began with Robin Hood! Disney appropriated the term 'Classic' for the initial release of Robin Hood (1973), which went into distribution in 1984 (Pallant 343). According to Frederick Wasser, in order to push Disney to the top rank of the video markets, the studio sold the "Classics" for limited periods of time, maximizing sales. Essentially, the Studio "decided to make new Disney classics to replenish the old ones" (2001: 165, italics added).

The Disney-Formalist movement prioritized the following: artistic sophistication, 'realism' in characters and contexts, and above all, believability. Moreover, this "artistic paradigm" initially promoted by Snow White, eventually became known as "hyperrealism": a concept that champions lifelike movement (motor function) of the animation, which reflects both the actual movements of living-action models and the skill of the animator. Bambi, representative of the hyperrealist peak of Disney-Formalist animation. One of the best examples of this aesthetic style is the "Little April Showers" sequence in Bambi, which presents a visually striking depiction of a springtime downpour:

Falling water is photographed at night with a spotlight playing on it. The film is then put in a camera and enlaraged prints made. Cartoon rain is added and the splatters are accentuated. The effect is much more lifelike than pen-and-ink rain, yet retains characteristics of animation. (Iwerks and Kenworthy, 2001: 155-156)

In fact, not only did Disney make arrangements for real deer to be kept 'on the lot' as models for animators (Finch, 1995: 209), but also had Rico Lebrun come in to teach night classes on deer anatomy. Lebrun actually brought in the carcass of two day old fawn, in order to show how each layer corresponded with its motor function. Of course, many of the animators stopped attending these classes due to the unsettling aroma the carcass exuded (Thomas and Johnson, 1981: 339-41).

During the production of Snow White, animators first had difficulty achieving this "hyperreal" effect. Initially, Snow White's eyes resembled that of Betty Boop's (no surprise given that the creators of Betty Boop were hired to create Snow White). Over time, and with continuous input from females in the studio, Snow White evolved into the image we know and love today.

During the production of Snow White, animators first had difficulty achieving this "hyperreal" effect. Initially, Snow White's eyes resembled that of Betty Boop's (no surprise given that the creators of Betty Boop were hired to create Snow White). Over time, and with continuous input from females in the studio, Snow White evolved into the image we know and love today.

Although when we think of Snow White, we think of her in relation to "the fairest of them all", for Disney, she was the embodiment of "cuteness". In fact, Zack Schwartz, an animator during the "Golden Age" of Disney, remarks that the word 'cute' used to drive him crazy, as the word was "all over the studio" during the production of Snow White (Frayling et. al., 1997: 5). The initial drawing (illustration on the left) of Snow White in 1935, however, was too "sexy" for Walt Disney. He told the animators he wanted her innocence and wholesomeness to be emphasized, hence the change of costume (our Snow White is in "peasant" clothing) and her lips are no longer pouted.

Disney’s inspiration for Snow White and the Prince came from then-actress Janet Gaynor and then-actor Douglas Fairbank Jr., while the depiction of the Evil Queen was a mixture between William Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth and the Big Bad Wolf (Thomas 130).

The Wicked Queen Stepmother

While Disney’s version omits Snow White’s mother, the fairy tale describes her at the story’s onset, where she sits at the window sewing, during winter. Accidentally pricking her finger, the Queen watches as three drops of blood fall onto the snow; finding the contrast of the blood and the snow incredibly beautiful, the Queen wishes for a daughter “as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as this frame” (the frame referring to the Queen’s window, made of black ebony wood). As you may have guessed, Disney altered the simile[3] “as red as blood” to “lips red as the rose” perhaps as a way of minimizing the story’s already “bloody” undertones.

Although the Queen’s wish comes true, she dies in

childbirth. Not long after (and similar to Cinderella), the King remarries.

Like in Disney’s version, the fairy tale Queen Stepmother is fixated with her

beauty, a fixation continuously reinforced by her magic mirror that deems her

the “fairest of them all” (the Grimm’s version reading “fairest of all”).

However, according to the original fairy tale, even at the age of seven, Snow White is far more

beautiful than her Stepmother. Angry to have lost her title to a child, the

Queen orders the Huntsman to have Snow White killed. While Disney’s Queen

demands that the Huntsman bring back Snow White’s heart (representative of the

heart that the Queen did not possess), the fairy tale’s Queen demanded

Snow White’s liver and lungs so she

could cook and subsequently consume them.

However, according to the original fairy tale, even at the age of seven, Snow White is far more

beautiful than her Stepmother. Angry to have lost her title to a child, the

Queen orders the Huntsman to have Snow White killed. While Disney’s Queen

demands that the Huntsman bring back Snow White’s heart (representative of the

heart that the Queen did not possess), the fairy tale’s Queen demanded

Snow White’s liver and lungs so she

could cook and subsequently consume them.

Although the fairy tale does not specify why

the Queen would wish to do this, it was once believed that by consuming the

organs of another human being, you would magically gain their qualities.

Although certainly an unsettling subject (and why Disney did away with it), cannibalism also crops up in the fairy

tale Sleeping Beauty, which we will

discuss later on in this lesson.

Although the fairy tale does not specify why

the Queen would wish to do this, it was once believed that by consuming the

organs of another human being, you would magically gain their qualities.

Although certainly an unsettling subject (and why Disney did away with it), cannibalism also crops up in the fairy

tale Sleeping Beauty, which we will

discuss later on in this lesson.

Unlike Disney’s version, the fairy tale describes the

Queen’s attempt to murder Snow White on four separate occasions. The first

instance being an indirect attempt—through the Huntsman. However, the fairy

tale’s description of the Huntsman’s encounter with Snow White is quite

different from Disney’s portrayal. Although the Huntsman, in both versions,

cannot bring himself to kill Snow White, the fairy tale describes the seven

year-old Snow White as far more aware and in control of her own life.

In the

fairy tale, Snow White puts two and two together on her own; she realizes the

Queen has sent the Huntsman and begs for her own life. In the film, it is Snow

White’s scream (both in confusion

and terror) that weakens the Huntsman’s resolve. In the fairy tale, it is Snow

White herself who suggests that she run away, not the Huntsman. Despite her

age, the fairy tale’s Snow White is mature and sure of herself, while Disney’s

adolescent Snow White is more in line with our conception of the “Damsel in

Distress” motif (which Hollywood picked up on and revamped in its depiction of the 2012 film Snow White and the Huntsman, starring Kristen Stewart and Chris Hemsworth).

In the

fairy tale, Snow White puts two and two together on her own; she realizes the

Queen has sent the Huntsman and begs for her own life. In the film, it is Snow

White’s scream (both in confusion

and terror) that weakens the Huntsman’s resolve. In the fairy tale, it is Snow

White herself who suggests that she run away, not the Huntsman. Despite her

age, the fairy tale’s Snow White is mature and sure of herself, while Disney’s

adolescent Snow White is more in line with our conception of the “Damsel in

Distress” motif (which Hollywood picked up on and revamped in its depiction of the 2012 film Snow White and the Huntsman, starring Kristen Stewart and Chris Hemsworth).

The next three attempted murders continue this motif, as Snow White is

repeatedly in peril, and the dwarfs must save her. Although Disney’s version

only depicts one of the Queen’s direct attempts at killing Snow White, the

fairy tale depicts two more attempts before this. In the fairy tale, instead of using magic to disguise her like in Disney's version,

the Queen merely dresses up as an old woman.

She appears at the dwarf’s cottage

selling bodice laces[4]. Snow White, of course, is home alone. The Queen laces Snow White so tightly she

cannot breathe and then leaves her to die. When the dwarfs return, they cut the

laces in time to save her life. The Queen discovers that Snow White is still

alive through her magic mirror. She then returns

to the cottage, this time with a poisoned

comb. Although now weary of strangers, Snow White allows the disguised

Queen inside, distracted by the beautiful comb. When the comb touches her hair,

she passes out, and the Queen departs once more. And, just as the first time,

the dwarfs return and remove the comb from Snow White’s hair and she awakens.

She appears at the dwarf’s cottage

selling bodice laces[4]. Snow White, of course, is home alone. The Queen laces Snow White so tightly she

cannot breathe and then leaves her to die. When the dwarfs return, they cut the

laces in time to save her life. The Queen discovers that Snow White is still

alive through her magic mirror. She then returns

to the cottage, this time with a poisoned

comb. Although now weary of strangers, Snow White allows the disguised

Queen inside, distracted by the beautiful comb. When the comb touches her hair,

she passes out, and the Queen departs once more. And, just as the first time,

the dwarfs return and remove the comb from Snow White’s hair and she awakens.

It is the last attempt—the poisoned

apple—that Disney’s version depicts. However, in the fairy tale, the Queen,

disguised as a peasant woman this time, offers to eat the other half of the apple as a sign of good will. In Disney’s

version, the Queen fools Snow White by telling her it’s a “magic” apple; one

bite will make any wish she makes come true.

It is the last attempt—the poisoned

apple—that Disney’s version depicts. However, in the fairy tale, the Queen,

disguised as a peasant woman this time, offers to eat the other half of the apple as a sign of good will. In Disney’s

version, the Queen fools Snow White by telling her it’s a “magic” apple; one

bite will make any wish she makes come true.

The Seven Dwarfs

In the fairy tale, the dwarfs offer Snow White shelter as an exchange for her services. They say, “If you will keep house for us, and cook, make beds, wash, sew, and knit, and keep everything clean and orderly, then you can stay with us, and you shall have everything that you want”. Yet the dwarfs’ house is spotless when she arrives; this signifies that, as much as they genuinely wish to help Snow White, they expect her to earn her keep. In a sense, this is quite similar to how many of our own parents have raised us. At least, mine certainly did!

In Disney’s version, Snow White offers her services to the

dwarfs (whose house is a mess when she first arrives). Given that the film was

produced during an economic depression, Snow

White was more than just a romantic fairy tale; it ultimately promoted a utopian alternative to the existing social

order, one which offered everyone

the chance to achieve success (as long as they were willing to work for it).

In Disney’s version, Snow White offers her services to the

dwarfs (whose house is a mess when she first arrives). Given that the film was

produced during an economic depression, Snow

White was more than just a romantic fairy tale; it ultimately promoted a utopian alternative to the existing social

order, one which offered everyone

the chance to achieve success (as long as they were willing to work for it).

It

is no wonder, then, that the songs “Heigh Ho”

and “Whistle While You Work” became popular hit tunes when

the film hit theatres (Thomas 143). Disney made us believe that if we all

worked “cheerfully together to tidy up the place”, we could—one day—change the

world.

It

is no wonder, then, that the songs “Heigh Ho”

and “Whistle While You Work” became popular hit tunes when

the film hit theatres (Thomas 143). Disney made us believe that if we all

worked “cheerfully together to tidy up the place”, we could—one day—change the

world.

Moreover, in Disney’s version, the dwarfs have their own “unique” personalities (named according to each of their characteristics), but in the fairy tale, there is very little that sets them apart--though both versions of “Grumpy” think all women are “trouble”.

The original names of the Dwarfs were actually "Burpy, Flabby, Wheezy, Dirty, Awful, Gaspy, Jaunty, Stuffy, and Shifty"--a far cry from our Happy, Dopey, Sleepy, Sneezy, Bashful, Grumpy, and Doc! In fact, the voice actor who played Sleepy and Grumpy was none other than Pinto Colvig, otherwise known as the voice of Goofy!

While Disney uses the dwarfs for the laughs (and the sentiment), in the fairy tale, they are mostly a means to an end.

As an incentive for their creativity, Disney’s animators participated in “Five bucks a gag”—a fun competition involving coming up with the best “gag” to offset more serious moments. Whatever animator’s gag Disney liked best, he/she would win the $5 (equivalent to about $50-$100 today). For example, Ward Kimball, one of Disney’s animators, came up with the moment depicted below and “won” $5 for it. As each of the dwarfs raise their heads, each nose “pops” over the beds one by one.

Snow White’s "Prince Charming"

While animation of the dwarfs was fairly straightforward, the

animation of the Prince (nameless, though some say Disney once referred to him as "Florian" not Ferdinand--that's the bull!) on the other hand, proved to be quite difficult.

As film

production went on, the Prince’s role in the film kept being scaled back to the

point where the animated Prince’s secondary role reflected that of the Prince’s

role in the actual fairy tale—practically non-existent.

In Disney’s version, the appearance of the Prince is the source of conflict itself: the Queen becomes jealous of the Prince’s interest in Snow White and seeks to have her killed; however, in the fairy tale, the Prince only appears at the end of the story, when Snow White has already been poisoned.

While happening across her comatose body entombed in a glass

coffin, the Prince learns, via the coffin’s inscription (engraved by the

dwarfs), that Snow White is the “daughter of a king”. The Prince then attempts

to purchase her body from the dwarfs. After transporting Snow White’s corpse

back to his kingdom, the Prince has his servants carry her coffin wherever he goes. In their frustration

at having to constantly carry around a seemingly dead girl, the servants open

the glass coffin in order to hit her.

What awakens Snow White is not “true

love’s kiss” (a motif most likely taken from Perrault’s Sleeping Beauty), but the jarring of the poisoned apple from her

mouth, which was still, somehow, lodged there after all that time.

Upon awakening,

she marries the Prince, who had, until that very moment, been entirely unknown to

her. In medieval Europe, of course, this was a common practice: the betrothal

of noble children while still in their cradles (as seen in Disney’s Sleeping Beauty). In order to

“modernize” the fairy tale, Disney decided that it was “more romantic” if

the lovers met—aka “love at first sight”—before their final kiss (Thomas 28).

Upon awakening,

she marries the Prince, who had, until that very moment, been entirely unknown to

her. In medieval Europe, of course, this was a common practice: the betrothal

of noble children while still in their cradles (as seen in Disney’s Sleeping Beauty). In order to

“modernize” the fairy tale, Disney decided that it was “more romantic” if

the lovers met—aka “love at first sight”—before their final kiss (Thomas 28).

The actual fairy tale, however, does not end with the Prince

and Snow White riding off into the sunset; instead, it closes with Snow White’s

Stepmother discovering, through her mirror, that she is still not the fairest of them all, for there is a new “young Queen”

in another land. Driven to the wedding by her jealously, the Queen discovers

that it is none other than Snow White, alive once again.

As punishment for her crimes against Snow White, the Queen is fitted with a pair of iron shoes that were recently put into the fire. She is made to wear these scorching hot shoes and to dance in them. The fairy tale ends with the evil Queen dancing herself to death. Disney's version, instead, depicts the Queen plummeting to her death.

Now that’s a show-stopping number!

Snow White’s Legacy

When

the animators were working on the scene where Snow White runs through the

forest and falls through a hole, they passionately debated over how far the

fall would be.

One

animator then asked: “But wouldn’t a fall like that kill her?”

One

animator then asked: “But wouldn’t a fall like that kill her?”

Upon uttering this question, there was a moment of silence; it was then the animators suddenly realized they were worried about killing a cartoon character. Snow White was as real to the animators then as Harry Potter, and his entire world, is real to us now.

The

first screening of the film left the entire theatre in tears. Kimball later

remarked in an interview that he could hear people sobbing. He also described

everyone rising to their feet, cheering and applauding.

Almost 80 years later, Snow White is the 10th highest grossing movie of all time (when figures are adjusted for inflation) - making $1.7 billion in total. Snow White is also one of 11 fictional characters from movies to be honoured with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Disney’s

“greatest folly” had ultimately become his greatest triumph. In fact, Disney received an honorary Oscar statuette (and seven miniature ones) at the 11th Academy Awards in 1939 for Snow White. They were presented to him by then 10 year-old Shirley Temple.

Disney’s

“greatest folly” had ultimately become his greatest triumph. In fact, Disney received an honorary Oscar statuette (and seven miniature ones) at the 11th Academy Awards in 1939 for Snow White. They were presented to him by then 10 year-old Shirley Temple.

When Walt Disney was once asked to explain the secret of Snow White’s phenomenal appeal, he responded saying: “Everybody in the world was once a child, so in planning a new picture, we don’t think of grown-ups, and we don’t think of children, but just of that fine, clean, unspoiled spot down deep in every one of us that may be the world has made us forget, that may be our pictures can help recall.”

Given

today’s popular ABC’s Once Upon a Time, centering on the plot of Snow White and her “Prince Charming”, perhaps it is not

so difficult to understand why Disney chose it for his first full-length

animated feature.

Cinderella: “The Sweetest Story Ever Told”

On account of Disney’s

adaptation, audiences are more familiar with Charles Perrault’s 1697 version of

Cinderella (“Cendrillon”) and not the Brothers Grimm 1812 version.

In the Perrault version, Cinderella rides to the ball in a pumpkin pulled

by white mice transformed by Cinderella’s fairy godmother into a coach and

horses.

Like the film, Perrault’s version also requires Cinderella to be home by midnight otherwise Cinderella’s beautiful gown, and everything else, will revert back to its original state. Since the Disney version is based on Perrault’s and not Grimm’s, our lesson will focus on Perrault’s, but you are more than welcome to read Grimm’s version (though be warned: there is some self-mutilation).

Disney’s Cinderella opens with a female

narrator describing a “tiny kingdom” that is “peaceful, prosperous, and rich in

romance and tradition.” In a “stately chateau”, live a windowed gentleman and

his beautiful daughter, Cinderella. Although Cinderella’s father is a loving

and devoted father, he feels that his daughter needs a mother and so he marries

again. The woman, Lady Tremaine, has two daughters: Anastasia and Drusilla (though in Perrault's version, only one is named: Charlotte).

While Disney’s version does not

differ much from Perrault’s, the primary differences lie in the fact that, in

Perrault’s version, Cinderella’s father is still alive and that the royal ball is

two nights, instead of one. In Perrault’s version, we get very little of the

stepmother; all we know is that she employs Cinderella in the “meanest work of

the house” (including cleaning the dishes, tables, chambers, floors, etc.). She

also forces Cinderella to sleep on a “sorry garret” (a wretched straw bed)

while her own daughters sleep in fine rooms with large looking glass mirrors.

The reason the narrator gives for Cinderella not going to her father for help

is that he would “scold” her as the stepmother “governed” Cinderella’s father “entirely”.

This is fairly disheartening that Cinderella’s father would listen to the

stepmother above his own beloved daughter, which no doubt explains why Disney’s

writers chose to depict the “untimely death” of her father instead.

Moreover, in Disney’s version,

Lady Tremaine is certainly the center of the film’s villainy; even her voice and

appearance appear threatening.

Moreover, in Disney’s version,

Lady Tremaine is certainly the center of the film’s villainy; even her voice and

appearance appear threatening.

This is no surprise given that the voice actress of Lady Tremaine (Eleanor Audley) is the same actress who went on to do the voice for Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty. In fact, she was given the role of Maleficent because of her foreboding portrayal of Cinderella’s stepmother.

Disney’s version of Cinderella

seems to have much more “spunk” than the other founding princesses. While she

is still very much the martyr of Perrault’s version (remaining respectful

to her stepmother and rarely ever argues, even when she wishes to attend the

ball), Cinderella’s personality is not one entirely of contented sunshine like

Snow White and Princess Aurora (all their occasional crying aside).

Disney’s version of Cinderella

seems to have much more “spunk” than the other founding princesses. While she

is still very much the martyr of Perrault’s version (remaining respectful

to her stepmother and rarely ever argues, even when she wishes to attend the

ball), Cinderella’s personality is not one entirely of contented sunshine like

Snow White and Princess Aurora (all their occasional crying aside).

This scene nicely depicts the contrast between her “Princess” nature and her individuality:

(A Google drive link to the video: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B2G0AXwWmqUcZzFyV21DREljRDA/view?usp=sharing).

Her anger at the clock, as opposed to her awful stepmother and stepsisters, suggests that she understands her situation much better than most other Disney Princesses. Although Cinderella is certainly frustrated by the fact that she is a “slave to time”, as all her daily chores must be completed in order to satisfy her stepmother, framing time as Cinderella’s enemy (as opposed to an actual person) suggests that she is a victim of her own time. With no real legal guardian, her status and money are taken from her and she is left with no choice but to remain a servant in her own home.

While not explicitly stated, Cinderella appears to understand this, infusing new meaning into her own “motto”: “A dream is a wish your heart makes.” Cinderella passionately declares, “They can’t order me to stop dreaming” demonstrating that, while she accepts the reality of her situation, she understands that the world has more to offer. By bearing her situation, she recognizes that her patience and hard work may one day pay off. This idea is certainly more in line with Perrault’s moral messages, which we will discuss towards the end of this section on Cinderella.

Of course, like Snow White and

Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella attracts a brood of animals that help her endure

her situation. However, Cinderella’s mice talk and have individual

personalities of their own. In caring for them like her own family, we gain

more insight to Cinderella’s character: like the mice, Cinderella feels like an “unwanted”

being in the household.

She clearly identifies with them and therefore watches over them, as they too watch over her by helping her get ready and providing her with companionship when things get rough.

In contrast to the mice, birds, and Bruno (the family dog), Lucifer—Lady Tremaine’s cat—is as mean and spoiled as the stepsisters, so he is certainly aptly named. By including animals with personalities, Disney’s writers actually channel Grimm’s version, which includes birds that interfere on Cinderella’s behalf. Disney’s version uses the mice as a way to emphasize the cruelty of her stepmother and stepsisters. Cinderella is immediately blamed for the “vicious practical joke” of Gus, the mouse, appearing under one of the stepsister’s teacups.

Cinderella is shocked

by the incident, and immediately scolds Lucifer, demanding that he release Gus.

As Cinderella’s stepmother piles on the workload, Disney sees to it that justice is ‘served’, so to speak, when Lady Tremaine finishes her list by adding, “Oh, see to it that Lucifer gets his bath.” Take that, you mean old cat!

Disney also introduces another storyline: the hot-tempered King and his fixation with his son getting married so he can finally have those grandchildren!

The Prince appears to possess “silly

romantic ideas” (anticipating Sleeping Beauty’s Prince Phillip) which is why it’s

taken him so long to find someone to settle down with. The King doesn’t appear

to be concerned with his son marrying a Princess, however.

While Perrault’s version states that the “king’s son gave a ball” and invited all people of “fashion”, there is no explanation for it. Disney’s version, however, is a “set up”. The King’s son is to return that evening and he schemes to throw a ball in celebration. Of course, if the “most eligible maidens in the kingdom” happen to be there, all the better.

While the King dismisses his own son’s romantic notions, he appears to be a romantic in his own right: he “sets the scene” by describing soft lights, romantic music (and gestures violins playing), and “all the trimmings” that a royal ball might have. While certainly a manipulative act, the King appears to go to a lot of trouble to ensure that the potential encounter is as romantic as it could possibly be. While you might think that this is more in line with a Princess’ fantasy, it is interesting that a King and Prince are so preoccupied with falling in love, while Cinderella merely dreams of a life beyond her prison, no thought whatsoever of a Prince to rescue her.

Back at the chateau, Cinderella is doing her best to tackle the mountain of chores. Her beautiful voice is a stark contrast from the shrill screeches of her stepsisters and their singing and flute lessons:

(Google Drive link to video: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B2G0AXwWmqUcMzNHMnRRbUdVMzg/view?usp=sharing ).

Another gutsy move by Cinderella is that she does, in fact, stand up for herself. While her stepsisters, like in Perrault’s version, tease her for wanting to go to the ball, unlike Perrault’s version, Cinderella makes a logical point:

“After all, I’m still a member of this family.”

In Perrault’s version, Cinderella’s father and stepmother aren’t even involved in the situation. In fact, they seem nowhere to be found. It is the stepsisters who force Cinderella to remain at home and don’t even give Cinderella the option to go. But Disney’s version breaks the façade Lady Tremaine has been keeping up all along: Cinderella is not, in fact, an actual servant, though she is treated like one. But like all Disney villains, Lady Tremaine has a plan: the conditional “if” is what is most cruel, as no person could possibly finish those chores, and get ready for a royal ball, in time. Especially when that person is also expected to help three other people get ready as well.

The dress that Cinderella pulls out of her trunk, as Cinderella says, once belonged to her mother. Growing up, I rarely caught this detail, not until I saw Ever After (1998) and wondered if Disney’s Cinderella had a trinket belonging to her mother as well. Perrault’s version makes very little reference to Cinderella’s mother, though the Grimm version begins with Cinderella’s dying mother who tells Cinderella to remain “pious and good” and that she will always be with her. It is the spirit of Cinderella’s mother that helps her along, but in Perrault’s version, it is the birds. In Disney’s version, as previously mentioned, it is the mice:

The mice are the ones who assemble Cinderella’s ballgown for her: a memorable eight minutes (including an extended sequence in which the mice collaborate to outwit Lucifer in getting the stepsisters’ ‘thrown away’ pink sash and blue beads). Along with the animals, Disney's version also channels Grimm's by including a stepmother who heaps tasks on Cinderella as a condition for her going to the ball (and the animals help her make it happen). One sixth of the original tale describes the animals helping Cinderella with her chores.

Despite their efforts in locating the “trimmin’” for “Cinderelly”, Cinderella’s stepmother finds yet another way to work her cruelty. She points out the beads, which one of the stepsisters threw away, which sparks one of the most tasteless outbursts in Disney cinematic history:

As cool as a cucumber, Cinderella's stepmother smiles after her daughters act monstrously and leaves Cinderella at home, her dress in pieces. Although you wouldn't necessarily know it on account of the stepmother's lack of magic, scholars describe her as a descendant of the Wicked Queen in Snow White. Magic or no magic, she's one cruel stepmother.

All seems lost for Cinderella after her "family" depart to the ball, and she despairingly declares that there is nothing left to believe in. But she couldn’t have lost all her faith, as her fairy godmother suddenly appears on the scene. Both Perrault’s and Disney’s version spend a considerable amount of time on the transformation (which I will discuss more in detail later on):

Even after the fairy godmother emphasizes that the spell will only last until midnight, Cinderella, in all her grace and gratefulness, remarks that it’s “more than she ever hoped for”.

As Cinderella rushes to the ball, the Prince appears completely bored (he yawns!) as he is introduced to the number of “eligible” maidens. The King looks on in anger and frustration at his son’s unwillingness to “cooperate”. Cinderella’s entrance into the castle is certainly memorable: it best reflects Perrault’s version of the music stopping and all eyes turning towards her. Yet Disney is certainly self-reflexive of this motif. The moment is “framed” by the Grand Duke describing the King’s “incurably romantic” nature by “narrating” the setting (without realizing he is doing so).

In his excitement, the King almost falls over the balcony in his attempt to “set the mood” for his son and potential mother of his grandchildren.

When the clock strikes midnight, Cinderella realizes she needs to get out of there as soon as possible. She awkwardly excuses herself by saying she hasn’t met the Prince yet (which might lead the Prince to think that she’s a gold digger), and he immediately tries to explain to her that he is the Prince, but then seems more desperate to discover her identity and where to find her.

While we imagine the story of Cinderella entirely resting on this one night, Perrault’s version describes Cinderella attending the ball which is two nights long. During her first night at the ball, while Cinderella does spend some time dancing with the Prince (he spends the entire night outright staring at her), she spends more time with her stepsisters, “showing them a thousand civilities” by offering them “oranges and citrons” and leaves the ball at 11:45. The following night, having got so caught up in the Prince’s “compliments and kind speeches”, she hurries away and accidentally leaves one of her glass slippers behind. The guards at the gate were asked if they had seen a grand princess leave, but all they saw was a “poor country wench”.

This is a far cry from Disney’s epic

chase scene (driven, no doubt, by the fact that the King told the Grand Duke

that if anything should go wrong, the King would have the Grand Duke's head).

This is a far cry from Disney’s epic

chase scene (driven, no doubt, by the fact that the King told the Grand Duke

that if anything should go wrong, the King would have the Grand Duke's head).

Transforming

back, mid-way, through the chase, Cinderella and her animal friends rush off

into the bushes to avoid getting trampled by the palace horsemen. However, one

thing remains from her evening: the single glass slipper—the magical symbol of

all future Cinderella stories.

While the King dreams of

frolicking with his grandchildren, the Grand Duke is the one to break the bad

news. With a modern reference to “blood pressure”, the King goes ballistic at

discovering the mysterious maiden has disappeared. However, thanks to the glass

slipper, all is not lost. The King assigns the Grand Duke the job of hunting

down the Prince’s future bride. During the hilarious bouncing up and down on

the King’s bed scene, the Grand Duke informs the King that the Prince will

marry none but the girl who fits the glass slipper (which is precisely what

Perrault’s Prince says as well). The Grand Duke's orders are clear:

“If the shoe fits—bring her in.”

Disney, of course, adds to our suspense: in another act of cruelty, Lady Tremaine, upon realizing that it was Cinderella at the ball, locks her in her room. It is the mice, and not any Prince, who must come to Cinderella’s rescue in time so she can try on the glass slipper.

To stall time, the Grand Duke falls asleep and the stepsisters do their best to cram the slipper onto their respective feet, while showcasing their "pleasant" personalities by hitting the footman multiple times over the head. To build even more suspense, Lucifer traps Gus under a cup, trapping him and preventing Cinderella from getting the key. The birds then fly off to get Bruno to ‘take care’ of Lucifer--something he's always wanted to finally do. The two scuffle and Lucifer ends up falling out the tower’s window. After all, Lucifer was the "angel" who "fell" from heaven!

In Perrault’s version, when

Cinderella is offered the opportunity to try on the slipper, she pulls out the

matching one and her godmother appears to magically transform her outfit once

more. Her stepsisters fall at her feet, begging her forgiveness. In a

magnanimous act, Cinderella forgives her sisters and brings them with her to

the palace, where they are introduced, and married off to, great lords of the

court. In Grimm's version, their eyes are pecked out by the birds as punishment for their actions.

In Disney’s version, we are given

another twist: freed from her room, Cinderella makes it downstairs in

time to try on the slipper. However, in yet another malicious attempt to

destroy Cinderella’s happily ever after, Lady Tremaine trips the footman, and

the glass slipper shatters. The Grand Duke thinks all is lost until

Cinderella pulls out the matching slipper. The best parts of this scene, of

course, is the image of the slipper being put onto Cinderella’s foot and Lady

Tremaine’s face when she realizes she has lost once and for all.

In Disney’s version, we are given

another twist: freed from her room, Cinderella makes it downstairs in

time to try on the slipper. However, in yet another malicious attempt to

destroy Cinderella’s happily ever after, Lady Tremaine trips the footman, and

the glass slipper shatters. The Grand Duke thinks all is lost until

Cinderella pulls out the matching slipper. The best parts of this scene, of

course, is the image of the slipper being put onto Cinderella’s foot and Lady

Tremaine’s face when she realizes she has lost once and for all.

While we all know that Cinderella and the Prince get married, Disney decided to produce two sequels: Dreams Come True and A Twist in Time. The former is merely a series of stories (one involving Cinderella planning a party while the King and Prince are away) and the latter involves Anastasia stealing the fairy godmother's wand and altering the original timeline, disrupting Cinderella's chance at seeing the Prince again and almost ruining her chance at happiness forever. However, Anastasia's conscience thankfully prevents Lady Tremaine from having her way and Cinderella and her Prince reunite once more. Even in an alternate timeline, Cinderella and her Prince are meant to be!

While we all know that Cinderella and the Prince get married, Disney decided to produce two sequels: Dreams Come True and A Twist in Time. The former is merely a series of stories (one involving Cinderella planning a party while the King and Prince are away) and the latter involves Anastasia stealing the fairy godmother's wand and altering the original timeline, disrupting Cinderella's chance at seeing the Prince again and almost ruining her chance at happiness forever. However, Anastasia's conscience thankfully prevents Lady Tremaine from having her way and Cinderella and her Prince reunite once more. Even in an alternate timeline, Cinderella and her Prince are meant to be!

Modernizing Disney Animation

The release of Cinderella (1950) marked Disney’s return to feature-length animation for the first time since Bambi in 1942. Its release sparked a financial turning point for the studio, both artistically and financially (the film earned more money than Snow White). In fact, as some of you may know, Cinderella is credited with pulling the studio out of debt. Its release initiated a number of other classics, such as Alice in Wonderland (1951), Peter Pan (1953), and The Lady and the Tramp (1955).

Although scholars have identified more than 700 versions of Cinderella, Disney’s version draws from Perrault’s seventeenth century work (appearing first as a poem in 1694, and then in prose in 1697), as part of a collection that included Little Red Riding Hood and Sleeping Beauty. Perrault actually reworked these tales in his capacity as a writer and advisor on matters of architectural design in the court of King Louis XIV (“The Sun King”) (Zaruchhi 1989). In fact, Perrault’s inclusion of Cinderella’s fairy godmother reflects the court’s fascination with fairies. His version, on account of Disney, has become the dominate version in Western culture.

Its significant narrative and ideological differences include: elimination of violence, heightening of drama and magic, and emphasis on the didactic message. In many ways, according to W.R.S. Ralston, Perrault eliminated the “savage” elements of common folk tales and “naturalized it in the polite world” (32). Moreover, only in Perrault’s version was Cinderella’s slipper identified specifically as glass. While some scholars declare that Perrault mixed up his words--verre (glass) vs. vair (fur)--others assert that the glass slipper represents purity, and its subsequent breaking the foreshadowing of a marriage ritual (in Jewish weddings, the groom breaks a glass by smashing it with his foot).

As previously mentioned, Perrault’s tales had a moral and didactic purpose. In his own words, these stories “incorporate useful moral … the light story in which they were enveloped was chosen only to make them enter more agreeably into the imagination, and in a manner which both instructs and entertains” (120). For Cinderella, he declared two morals: one religious (the virtues of patience and kindness), the second more pragmatic (though perhaps not entirely realistic--that one can’t get ahead without a fairy godmother). Although we might not have a fairy godmother, we all certainly possess the strength and desire to pursue our dreams. Perrault’s version, therefore, was perfectly in line with previous (and of course future) Disney films.

Just as it was Disney who was entirely responsible for his initial success, it was also ultimately his decision to produce Cinderella that saved the studio. While Disney’s brother, the company’s president and chief financial officer, Roy Disney, argued that the studio should avoid feature animation (Miller 123), Walt desired to continue, though this time planning films five years in advance, instead of one. This decision forever changed the Disney film production process.

But Disney knew it would be time-consuming and financially draining; therefore, to control costs in the production of Cinderella, animators decided to film all of Cinderella in live action before animating it. The footage was used to check the plot, timing, and movements of the characters before any drawings were made (Ohmer 238). Although this certainly saved animators a lot of time, it ultimately limited their staging and camera angles: “Anytime you’d think of another way of staging the scene, they’d say: ‘We can’t get the camera up there!’ Well, you could get the animation camera up there! So you had to go with what worked well in live action” (Solomon 181).

Disney also conducted market research to “poll” audiences on their reaction to the initial drafts of their post-war films. They hired the Audience Research Institute (ARI) who conducted a “want-to-see” test to assess Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, and Peter Pan. Cinderella won with a rating of 95% (on a scale of 100), Peter Pan with 76% and Alice with 71%. On top of market research, Disney’s production team also hosted staff conferences, which included maintenance crews, secretaries, all the in-between assistants, the junior animators, and “women from ink and paint” (Ohmer 239). Although Disney did not attend all of these conferences, he thoroughly read the typed summaries of these conferences (many ranging from 20 to 30 pages long) so that he could keep tabs on Cinderella while he was involved on other projects.

An example of some of the feedback Disney received from his own employees included a complaint about the weak use of the animals characters: “The animals need to move the story, not dress it” (ARI files, June 27, 1947). This is actually quite incredible given that the final version of Cinderella includes developed storylines for Jaq and Gus and their frequent encounters with Lucifer. In fact, the animals receive more screen time than most of the human characters! It’s only after being 18 minutes into the film before we officially meet Cinderella’s stepmother and stepsisters--one quarter of the entire narrative!

Audiences and staff also contributed to the shaping and sequencing of the songs. By February 27, 1948, three songs had been formulated: “A Dream is a Wish”; “So This is Love”; and “Bibiddi Bobbidi Boo” (also known as the “Magic Song”). While some market research suggested the inclusion of a Jazz number, Disney was adamant that the film echo the romantic ballads of Snow White, a decade earlier.

While animators were concerned that Cinderella too closely resembled its initial live action counterpart (which is somewhat ironic, given the recent release of the live action Cinderella movie), the film successfully celebrates the power of animation on account of its fluid transitions between narrative temporal spaces; for example, Cinderella as child, Cinderella in her bedroom as an adult, as well as from her slipper fitting to the end marriage sequence. One of the most impressive sequences, however, is the fairy godmother’s magical transformations. The sequence lasts seven minutes (one tenth of the film), and was said to be Walt Disney’s absolute favourite (Ohmer 240).

The carriage should be dainty. The wheels shouldn’t be enough to hold the weight. We should feel that it’s a fairy carriage … Cut out all the excessive dialogue and work in some new dialogue for Cinderella in counter to the melody while she is crying. Have her run out and hit the spot, and as she is saying this, let the animals come up and get closer. Have them gather around in a sympathetic manner. They don’t know whether they should approach her or not … Have the miracle happen at the end of the song. ‘The dream that you wish will come true’ is where we start to bring the Fairy Godmother in. She materialises because she is there to grant the wish.

(Disney, quoted in Bob Thomas, Disney’s Art of Animation 1991: 100).

In Year 2 of Transfiguration, you learned about transfiguring living things into objects, including a mouse into a snuffbox. Yet Cinderella's fairy godmother does much more than transfigure a mouse; she transforms four mice into horses; a horse into a coachman; a dog into a footman; and a pumpkin into a carriage. Towards the end of Year 2, you learned about cross-species transfiguration and the potential harm you might cause animals with extremely different biological makeup. While Cinderella's fairy godmother is able to accomplish these acts of transfiguration in a matter of minutes, finishing it off with an artistic flare of transforming Cinderella's rags into a beautiful gown (with glass slippers to boot), none of you should ever attempt this unless you have spent years conducting in-depth research on both animals in question and worked towards specializing in transformative zoology. Transfiguring animals into humans, on the other hand, is extremely complex, powerful magic, as I am sure Professor Prince will tell you. If you wish to avoid severely injuring, or potentially killing any animal or human being, you should not attempt any of this magic until much later in your education. If you're interested in pursuing this subject further, you should consider continuing on with Transfiguration.

Of course, animators were worried that Cinderella was becoming too close to Snow White and they even briefly discussed the animals being a hindrance to Cinderella, rather than her helpmates just to enhance the difference between the two films. They were most intent on “correcting” the “sugariness” of Snow White’s character, desiring Cinderella to display a range of emotions. There were two specific issues the animators wished to address: “the fundamental contradiction between misery and fantasy in the narrative, and the film’s representation of romance” (Ohmer 244). One animator, in fact, stated that the film “had better give a good reason” for Cinderella’s tolerance of her stepfamily’s abuse. Early drafts of Cinderella included even harsher treatment, and even a scene where Cinderella visits her father’s crypt (evoking an entirely different feeling, more in line with Grimm’s version)!

To contrast the “drudgery” of Cinderella’s existence, animators added beautiful music and animation, particularly when Cinderella is washing the floor (before Lucifer makes a mess of things). They were actually considering cutting the lovely “Sing Sweet Nightingale” number because it was expensive to animate, but thankfully they decided to keep it after all. Extremely different from her other early Princess counterparts, Cinderella--according to one animator--is a girl “who actually has a lot of guts and stands up to tremendous adversity” (Parmet 76-78).

That same animator continued saying: “And then, of course, you have the magic.”

Although Disney’s Cinderella seemed to gesture towards the past and carried on the studio’s traditions, its advanced and "magical" animation continues to capture our hearts 65 years later, and also paved the way for even more ambitious projects, such as Sleeping Beauty.

Sleeping Beauty: Named after the Dawn, gifted with Beauty and Song

The

film opens with a male narrator, who introduces us to newly born Princess

Aurora and the subsequent celebration of her birth. In Charles Perrault's version of Sleeping Beauty, the name Aurora ("Aurore") is actually the name of Sleeping Beauty's daughter, and her son, "Jour" (after the day) because he seemed even more beautiful than his sister.

The film’s opening song

(besides the opening credits), “Hail to the Princess Aurora”, emphasizes the

film’s setting: the medieval world.

During the celebration, the neighbouring King (Hubert) and his son, Prince Phillip, arrive in order to bestow upon Aurora their gifts. As previously mentioned in the section on Snow White, Prince Phillip and Aurora are betrothed.

Phillip is, based on his appearance, at least seven to 10 years older than Aurora. On Aurora’s 16th birthday, Phillip would therefore be around 23-25 years old. At this time, the difference in age was common. Even in today’s world, the age of consent is 16 years old.

Phillip is, based on his appearance, at least seven to 10 years older than Aurora. On Aurora’s 16th birthday, Phillip would therefore be around 23-25 years old. At this time, the difference in age was common. Even in today’s world, the age of consent is 16 years old.

Before Merryweather can bestow her gift on the Princess, Maleficent arrives. She expresses her “distress” at not receiving an invitation, given that “royalty, the nobility, the gentry, and even the rebel”

(a dig at the three fairies) are present.

In Perrault's version, Maleficent had not been seen "for more than fifth years" since she had not left her Tower and she was "believed to be dead or enchanted" (186). While Perrault's Maleficent didn't seem to have much of a case for being angry at not being invited to the Princess' baptism, Disney's Maleficent appears to have already been feared by the entire kingdom, and Merryweather accurately asserts that she "wasn't wanted."

Determined, Merryweather alters the curse from death to sleep. In typical Disney fashion, declares “true love’s kiss” to be the magical undoing of Maleficent’s curse. For, as the chorus of voices sing at the end of this scene, “True love conquers all.”

That night, all the spinning wheels in the kingdom are burned, as the three good fairies watch in dismay, knowing that Maleficent will find another way to see her curse fulfilled.

While the fairies toss around some ideas about outsmarting Maleficent (including transforming Aurora into a flower), they finally settle on disguising themselves as mortal peasant women, foregoing all magic in order to hide the Princess for the next 16 years. In all Maleficent's wickedness (Fauna smartly points out) Maleficent does not understand love, kindness, or the joy of helping others. The three fairies then sneak Aurora out of the castle that evening and raise her in an abandoned woodcutter’s cottage deep in the forest, re-naming her Briar Rose.

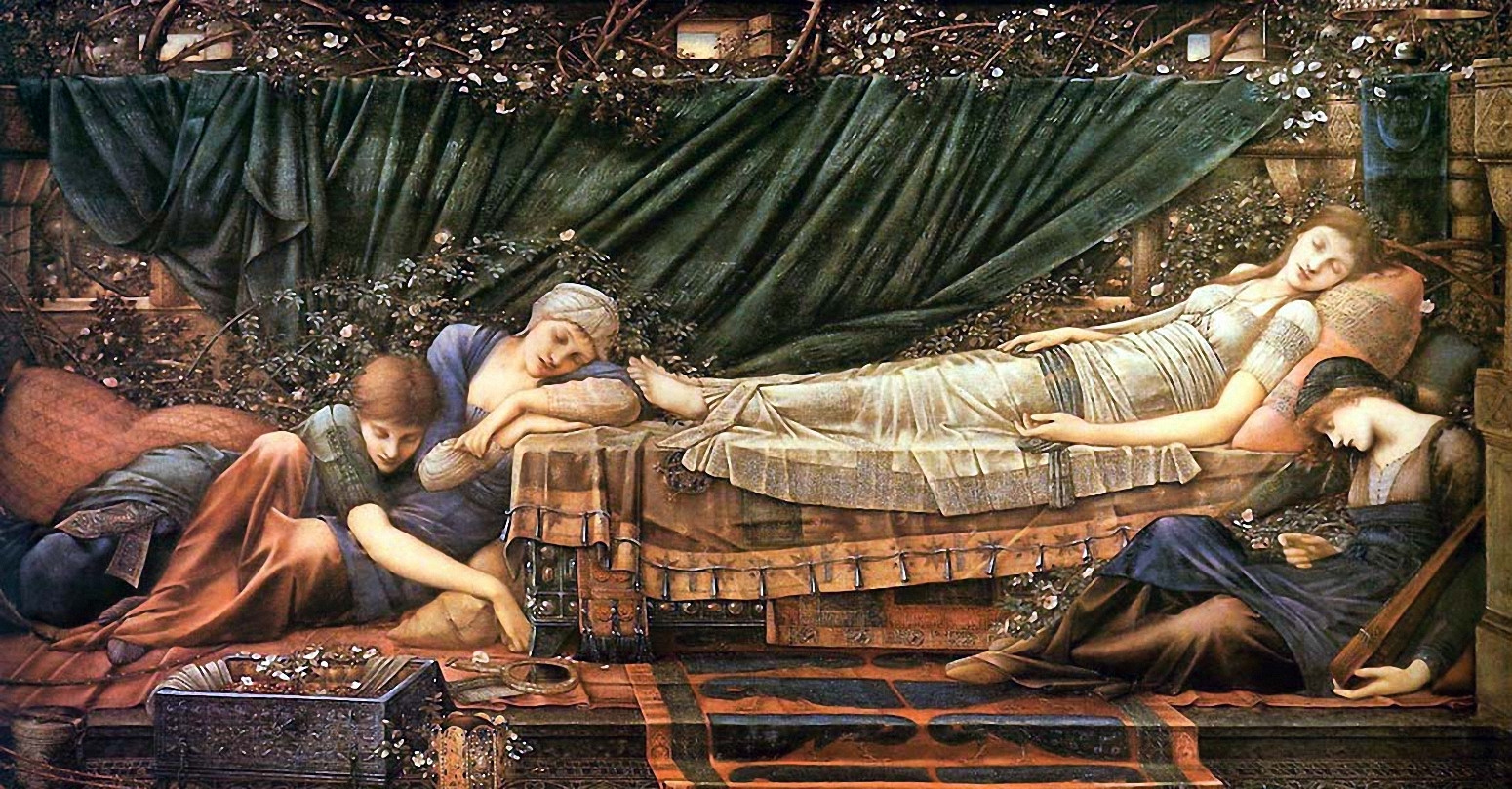

"Little Briar Rose" is the name Sleeping Beauty receives in the 1857 Grimm Brothers' Dornröschen ("Little Briar Rose"), though Disney's version is adapted from Perrault's. It is also the name that inspired many of Edward Burne-Jones' paintings of the literary and iconic figure of Sleeping Beauty.

As Tatar argues, the figure of Sleeping Beauty ultimately is "the Briar Rose"--"the woman who engages in a reciprocal metaphorical relationship

with the thickets or roses and thorns encircling the castle and who incarnates

in her stillness the seductive pull of beauty and death” (152). For many scholars, the figure of Sleeping Beauty embodies both the beauty of suffering, and the suffering for beauty. While Aurora certainly isn't cursed on account of her beauty, she represents, at least for Maleficent, all the goodness, purity, and potential beauty of the world that Maleficent wished to destroy.

As Tatar argues, the figure of Sleeping Beauty ultimately is "the Briar Rose"--"the woman who engages in a reciprocal metaphorical relationship

with the thickets or roses and thorns encircling the castle and who incarnates

in her stillness the seductive pull of beauty and death” (152). For many scholars, the figure of Sleeping Beauty embodies both the beauty of suffering, and the suffering for beauty. While Aurora certainly isn't cursed on account of her beauty, she represents, at least for Maleficent, all the goodness, purity, and potential beauty of the world that Maleficent wished to destroy.

Sixteen years pass, and the Kingdom begins to prepare for Aurora’s return since Maleficent’s prophecy has not yet come to pass. Of course, this has more to do with the fact that Maleficent’s henchmen have been searching “every cradle” for the last sixteen years. Outraged and frustrated by her henchmen’s “disgrace to the forces of evil,” Maleficent sends her devoted pet raven to find the fair maiden. Maleficent's repeated depending on "lower being" creatures to do her dirty work is obviously a means to extend the plot, because she could just as easily locate Aurora herself if she wanted.

In all this time, the fairies have raised Briar Rose without magic (though how they managed is beyond me, given that Merryweather claims that neither Flora nor Fauna learned to sew or cook in all that time as they make preparations for Briar Rose’s 16th birthday party). Excited but saddened by the approach of Aurora’s birthday, the good fairies send Briar Rose out of the house to collect berries.

While discussing with her animal friends her “Dream” Prince, Phillip surprises her (much like Snow White’s Prince—“I didn’t mean to frighten you”) and they dance and sing together. This number, which came to be known to the animators as "Sequence 8", was the film's most lengthy in production. It was one of the first sequences made, but since things were still being ironed out, it was the last part sequence to be completed in final colour. It then went on to become one of the film's signature scenes.

When Rose returns, the fairies reveal to her that she is Princess

Aurora, engaged to Prince Phillip. Too distraught at learning she will

never see the man in the woods again, Aurora takes to her room. While the fairies prepare Aurora to leave, King Hubert and King Stefan discuss their plans for their children. Their marriage as well as their honeymoon “cottage” (which is a "small" castle with 40 rooms) seems to have already been built, but King Stefan, who has not seen his daughter in 16 years, tries to make Hubert see reason. The two argue, but eventually make up.

When Rose returns, the fairies reveal to her that she is Princess

Aurora, engaged to Prince Phillip. Too distraught at learning she will

never see the man in the woods again, Aurora takes to her room. While the fairies prepare Aurora to leave, King Hubert and King Stefan discuss their plans for their children. Their marriage as well as their honeymoon “cottage” (which is a "small" castle with 40 rooms) seems to have already been built, but King Stefan, who has not seen his daughter in 16 years, tries to make Hubert see reason. The two argue, but eventually make up.  Prince Phillip returns to the castle to tell his father that he’s in love with a peasant girl. Outraged, King Hubert declares a Prince should marry a Princess. Laughing at his father, Prince Phillip responds, “Why father, you’re living in the past. This is the 14th century!” Although certainly a self-reflexive reminder that Sleeping Beauty is set in the late Medieval Ages, its humour is actually rather dark given the fact that the 14th century was marked by famine, war, and The Black Death. Technically, a cursed newborn princess would have been the least of a Kingdom's problems.

Prince Phillip returns to the castle to tell his father that he’s in love with a peasant girl. Outraged, King Hubert declares a Prince should marry a Princess. Laughing at his father, Prince Phillip responds, “Why father, you’re living in the past. This is the 14th century!” Although certainly a self-reflexive reminder that Sleeping Beauty is set in the late Medieval Ages, its humour is actually rather dark given the fact that the 14th century was marked by famine, war, and The Black Death. Technically, a cursed newborn princess would have been the least of a Kingdom's problems.

Before Hubert can reason with his son, Phillip is off again to see the ‘girl of his dreams’. But by now Aurora is already in the castle, dressed as a Princess. The good fairies leave her to come to terms with the situation, only to discover that, in leaving her alone, they have given Maleficent the perfect opportunity to place Aurora under an enchantment, quite similar to the Imperius curse in the world of Harry Potter.

Before Hubert can reason with his son, Phillip is off again to see the ‘girl of his dreams’. But by now Aurora is already in the castle, dressed as a Princess. The good fairies leave her to come to terms with the situation, only to discover that, in leaving her alone, they have given Maleficent the perfect opportunity to place Aurora under an enchantment, quite similar to the Imperius curse in the world of Harry Potter.

Frantic to stop Rose before she “touches anything”, the fairies chase Aurora up the tower, only to discover that they are too late. Maleficent disappears in a flash of green light and the fairies are left with no choice but to cast a sleeping spell over the entire Kingdom, almost forgetting about Merryweather's "true love's kiss" clause in their grief as they place Aurora in her bed, completing the iconic "Sleeping Beauty" scene depicted throughout history.

As they cast their sleeping spell, the fairies have just about given up hope, until Flora overhears Hubert talking to King Stefan about Prince Phillip’s encounter with “some peasant girl” and their meeting "Once upon a dream". Flora puts two and two together and the three fairies return to the cottage.

Of course, Maleficent’s raven having already learned of Aurora’s love interest, Maleficent beats them there. She too is surprised to discover that it was Prince Phillip all along. When the fairies discover that Phillip has been captured, they seek to rescue him at “The Forbidden Mountain”—Maleficent’s domain. Upon rescuing the Prince, Flora bestows upon him two gifts: the Enchanted Shield of Virtue and the Mighty Sword of Truth. These “righteous” weapons will triumph over evil.

The three fairies use their magic to prevent Philip from harm: they transform boulders into bubbles, arrows into flowers, and boiling oil into a rainbow--all forms of defensive magic, which allows Prince Phillip to escape Maleficent's domain. Much of the three fairies defensive magic is similar to Dumbledore’s tactics when he faces down Voldemort in the Ministry of Magic. Their intention, clearly, is not to harm, but to protect.

The three fairies use their magic to prevent Philip from harm: they transform boulders into bubbles, arrows into flowers, and boiling oil into a rainbow--all forms of defensive magic, which allows Prince Phillip to escape Maleficent's domain. Much of the three fairies defensive magic is similar to Dumbledore’s tactics when he faces down Voldemort in the Ministry of Magic. Their intention, clearly, is not to harm, but to protect.

As Prince Phillip and the three fairies make their way out of Maleficent’s domain, Maleficent, in one of the most epic Disney battle scenes, surrounds Stefan’s castle with thorns and then hurls herself across the countryside, appearing in front of him in dragon form. In Transfiguration Year 3, you learned about an advanced form of transfiguration involving the transformation of a human into an animal, specifically animagi. An animagus is a witch or wizard that can change their form at will into that of an animal without a wand or incantation. As some of you already know, the animal shape is not a choice of the person, but rather a manifestation of a physical trait of that specific person.

As Prince Phillip and the three fairies make their way out of Maleficent’s domain, Maleficent, in one of the most epic Disney battle scenes, surrounds Stefan’s castle with thorns and then hurls herself across the countryside, appearing in front of him in dragon form. In Transfiguration Year 3, you learned about an advanced form of transfiguration involving the transformation of a human into an animal, specifically animagi. An animagus is a witch or wizard that can change their form at will into that of an animal without a wand or incantation. As some of you already know, the animal shape is not a choice of the person, but rather a manifestation of a physical trait of that specific person.

Maleficent is an animagus of a particular kind, and her form is that of a dragon. While dragons possess stronger forms of magic than witches and wizards, Maleficent is a magical being who can call on “all the powers of hell”. As we have already seen, dabbling in the Dark Arts is something that should always be avoided. If you’re interested in studying to become an animagus, Professor Prince enthusiastically encourages you to pursue Transfiguration.

With one more spell from Flora onto the sword ("May evil die and good endure!"), Philip hurls it into the heart of Maleficent.

Upon kissing Aurora, the rest of the Kingdom awakens. The Prince and Princess appear before their parents, together for the first time, and they live, as they always do, happily ever after.

Once Upon a Dream

In 2008, Disney’s Sleeping Beauty celebrated its 50th Anniversary. It took almost nine years (1951-1959) to produce the film. Although it’s considered as one of the “founding” Disney Princess movies, this film, in terms of its animation, “doesn’t look like a Disney” on account of Eyvind Earle, the production designer who oversaw the film. Earle would often spend at least 10 days working on a backdrop—which would, on average, only take a single day to complete.

Most impressively, he painted the majority of the backgrounds himself. Remember that scene in Lady in the Tramp when Lady and Tramp wake up on a hill and look out over the town and beyond it? He painted this backdrop (left). The artwork is what differentiates Sleeping Beauty from other Disney films. While Snow White engages in hyperrealism, Sleeping Beauty is more suggestive of medieval illuminated manuscripts (something that Professor Honeysett will touch on in her visit during your lesson on The Sword in the Stone).

What is also particularly striking about the film is its subtle reference to contemporary popular culture. While Charles Perrault’s version of Sleeping Beauty does begin with the celebration of the birth of Princess Aurora, Disney’s version also introduces Aurora’s intended—Prince Phillip. He is named, of course, after his real-life counterpart: England’s Prince Phillip, with whom the world, at the time, was fixated due to his engagement to Queen Elizabeth. The couple secretly became engaged in 1946, and then formally engaged in 1947, when Queen Elizabeth turned 21. Given Disney’s connection to a real-life Prince, it is no surprise that the film has become a Disney classic.

Even today, the story of Sleeping Beauty lives on. Beyond its mention in ABC’s Once Upon a Time, the recent release of Maleficent, starring Angelina Jolie, re-invents the story once more, this time from the perspective of the fairy (yes, Maleficent, in Perrault’s version, is in fact a fairy!). Maleficent (“The Mistress of All Evil”), in Disney’s version, embodies pure malevolence. Although all Disney villains no doubt haunted many of our nightmares, Maleficent was, at least for me, the one that looked and felt to be the most terrifying.

"All the Powers of Hell"

The Diamond Edition of Sleeping Beauty reveals that the unsettling female voice that seems to call to Aurora as she makes her way through the fireplace, was actually speaking Aurora’s name. Listen closely to the digitally re-mastered edition (and watch the following review of the DVD - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nF1-Qehr4wM) and you will hear it. It wasn't until doing research for this lesson that I learned an actual name was being said, as opposed to a mythological Siren-like sound. In fact, the music that accompanies Aurora’s powerless trance-like state before pricking her finger, ‘till this day, still echoes in my head before I go to bed at night!

The medieval setting and frequent eerie music is certainly fitting, given that Perrault’s 1697 fairy tale—“La belle au bois dormant”—is both fascinating and disturbing, mostly due to the cannibalism storyline that has been dropped from the bulk of children’s versions of this fairytale. The original fairytale, after Sleeping Beauty comes out of her deep slumber, is threatened once more by an ogress mother-in-law. The Prince’s mother does not just act like an ogress—she is one, and she is determined to devour her daughter-in-law and her grandchildren. This “second” half of the story has forced scholars to assert that Perrault’s version is not one tale but two (Soriano 125). Disney’s version focuses only on the “first” half--sorry Hannibal fans! But Perrault does leave us with a final lesson:

Aspires to the conjugal trust,

That I have neither the strength nor the heart

To preach to her this moral."